When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

The Leadership Paradox of Principled Moderation

Allen Slade

I have previously argued that principles of leadership are outdated. These old school principles of leadership – all leaders should be tall, male, Theory Y, 9/9 or whatever – do not tend to maximize your influence in the real world.

I strongly believe that leadership theory has failed to come up with simple, one-size fits all rules for leaders. Because of the nature of leadership science, I suspect we will never have simple principles of leadership.

I am not arguing that leaders should be unprincipled. In fact, there are principles all leaders should pursue: principles of ethics and the principle of moderation.

Moderation is essential for your leadership. Leaders who believe in the one best way tend to drive into the ditch. For example, when making a decision, leaders can interact with their team in a number of ways. They can direct the team to action, consult with the team before deciding, ask the team to participate in the decision, delegate the decision or empower the team to take action on their own. In most organizations, a moderate amount of direction, consultation, participation, delegation and empowerment will work well.

Petronius said “Moderation in all things, including moderation.” Some people refer to this as a paradox. I see moderate moderation as a gentle warning of the dangers of absolute relativity. As a leader, at times you need to be a rock in the storm. You have to take a principled stand. The people you lead expect consistency in your behavior. You will develop your own set of ethical principles. As a thought starter, here are two principles I pursue in my own leadership:

Integrity. When I make a commitment to you, I follow through. I make SMART commitments when feasible, and I keep them. If something changes, I will proactively ask you if we can renegotiate. I do not cross my fingers or give myself a “silent” escape clause that would allow me to avoid you if times get tough. If I fail to keep my commitment, I do three things: apologize, state that it will not happen again and ask how I can make it right.

Appropriate Transparency. I say what I mean and I mean what I say. I let those I lead know about me, while avoiding too much information. I refuse to be interrogated, so I keep confidences with silence rather than falsehood.

Principled moderation is a potent combination. There are certain principles that should run through your leadership, like integrity. Yet, you should be moderate in most things. Your team will know what you stand for, and know that you will adjust your behavior to fit the situation. Then, you will be a rock in the storm and a shining example of moderation.

Many Mini-Experiments

Allen Slade

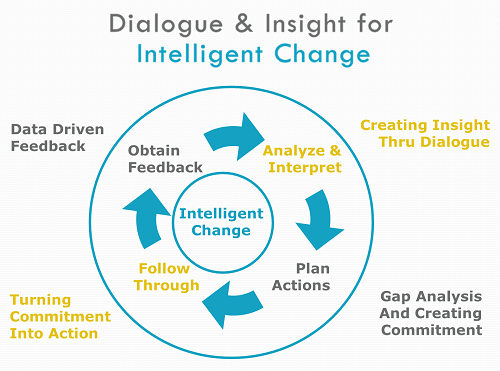

In Teachers, Mentors and Coaches, I made the case for the value of coaching for adults who want to grow as leaders. Teachers impart expertise. Mentors impart experience. Coaches create dialogue and insight for intelligent change. And a big part of what coaches do is to create mini-experiments.

Coaching dialogue is different from normal conversation. At the beginning, a client and I reconnect and check on previous mini-experiments. In the middle, we discuss the issues facing the client. I bring active listening, powerful questions and direct communication to the conversation. I do not bring an agenda. You, the client, set the agenda, because you are the expert in your own situation. If you want to talk about next week’s meeting, the marketing strategy, a difficult customer or the new IT system, I am good with that.

If the first 50 minutes are dialogue and insight, the last ten minutes are action planning. I work with my clients to create mini-experiments at the end of each coaching session. A mini-experiment is an action plan to try something new and different. For an executive, this might be a different approach to growth strategies. For a leader, it might be managing emotions before a speech. For a career coaching client, it could be a simulated interview. Since the client is the expert on the situation, I propose mini-experiments as a SMART request. The mini-experiment is SMART because it is specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. It is a request because the client can respond yes, no, offer to negotiate or decide later. We usually negotiate – the client raises valid concerns, and I ask “What would work?” Together, we create something SMART that can drive intelligent change.

Whether in the physics lab or the conference room, an experiment requires a hypothesis and measures. The hypothesis might be “If I do [something different], then my strategies/speech/interview will be better.” To figure out whether the hypothesis holds water, we need measures that produce data. The best data will compare the old way of doing things with the new way. This data needs to be credible and relevant to you the client, so that you are confident of your evaluation of the different way of doing things. We probably don’t need the rigor of a sophisticated experimental design or statistics. What works for you works for me as your coach.

A leadership coaching client was having difficulty with a key executive. Our coaching conversation hinged on how the executive fell short of expectations. However, my client saw the needs of his customers as an opportunity for creative problem solving and servant leadership. We reached a key insight: customer shortcomings were energizing but executive shortcomings were deflating. We designed a mini-experiment: “Think of your boss as your customer for the next week. See how that impacts your attitude toward your boss.” At our next coaching session, I checked on how the mini-experiment went. My client reported it was hard to think of his boss as a customer. But when he did, he had a more positive attitude, resulting in upward problem solving and service to his boss.

This was not a “bet your career” experiment. It happened to work. If it had not worked, we would have discussed why, and either tried the “boss as customer” idea again with a SMARTer action plan or else come up with a new approach. Because of minimal risk, quick turnaround and limited effort, you can do many mini-experiments.

Mini-experiments are planned actions driven by feedback, dialogue and insight. When the mini-experiment is completed, we have another round of feedback, dialogue and insight. And another mini-experiment. The beauty of many mini-experiments is something is bound to make a difference. That’s why we call it intelligent change.

Mini-experiments are planned actions driven by feedback, dialogue and insight. When the mini-experiment is completed, we have another round of feedback, dialogue and insight. And another mini-experiment. The beauty of many mini-experiments is something is bound to make a difference. That’s why we call it intelligent change.

Teachers, Mentors and Coaches

Allen Slade

Who sparks your growth as a leader? Who triggers dramatic turnarounds in your career?

As kids, growth was our job, but someone else set the agenda. Adults, including our parents and teachers, helped us climb the ladder to maturity. As we climbed, we took more responsibility for our own learning. The college professor did not manage our days like the kindergarten teacher. After college, we became even more specialized in skills, more complex in thinking and more diverse in motivation.

So, who has the biggest role in your learning today? A teacher? A mentor? A coach?

Teachers impart knowledge based on their expertise. The best teachers are subject matter experts with strong platform skills. They know the material and they know how to deliver it. Yet, corporate training classes suffer from a lack of transfer of training back to the work situation. Traditional teaching does not impact adults like it impacts 5-year olds. Adults need individualized, experienced-based growth.

Mentors impart wisdom based on their experience. Mentoring can be a powerful experience, sharing personalized knowledge and advice customized to the needs of the mentee or protégé. Yet, mentoring tends to be hit or miss. Most formal mentoring relationships do not make it past the second meeting.

At the extreme, teaching and mentoring requires adult learners to suspend their disbelief in their own expertise and experience. Teaching and mentoring are built on a shaky assumption:

You do not know what you need or how to get it. You need an expert teacher or an experienced mentor to guide your learning.

Our adult mindset resists returning to this child-like belief. “He got schooled” is a taunt rather than an effective training strategy. “Listen to your parents” grates on teenagers, so it is not surprising that mentoring often misfires for adults.

Coaches are different. A coach believes you are the expert in your own situation. Instead of giving you the answer, a coach is more likely to ask questions. Instead of setting goals for you, a coach will help you define your own goals. Instead of holding you accountable, a coach helps you hold yourself accountable.

Coaches give up control to gain influence. As a professor, I required my students to show up at the appointed time and place, ready to discuss the assigned readings. But once the final grades were in, my control ended and my influence largely disappeared. As a coach, my influence is soft but lasting. As a coach, I don’t tell people what to do, how to do it or when it is due. I just ask questions and share distinctions. I request behavioral agreements, but I encourage my client to say no to my requests. I do not enforce the agreements. I merely ask about the impact of not following through. Yet, the impact of coaching can be life-long, resulting in new thinking patterns, more effective habits and changed values, attitudes, beliefs and expectations.

Bottom line: Training and mentoring have limited impact on experienced professionals, leaders and executives. Coaching is more likely to maximize your leadership influence or trigger a career turnaround.

There are situations that call for training or mentoring. Training works well for transfer of knowledge, like learning a new online application. Mentoring is great for new hires. However, for most adults in most situations, coaching is more powerful than either teaching or mentoring.

The difficulty with coaching is cost. In comparison to one-on-one sessions with a certified coach, classroom training is cheap. Mentoring is free.

Cost is important, but not the only consideration, especially when we seek life changing assistance. We don’t typically look for the cheapest medical care. We turn to our company for health insurance. We don’t depend on free legal advice. We budget to pay for an attorney.

If you seek leadership coaching, take advantage of what your company offers. You may have an internal coaching program or a personal development budget.

If you seek career coaching, budget for it. Your return, in increased salary and life satisfaction, will be worth the investment.

Don’t wait for someone else to decide what you need. If you think you would benefit from coaching, you are right. You are right, not because you agree with some expert on coaching. You are right because you are the expert on your own growth.