When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Leading with Goals

Allen Slade

Goal setting should be one of the most useful tools in your leader’s tool box. Goals can drive intelligent dialogue about performance with your employees, leading to greater success and satisfaction for your employees and your organization. Here are some ways you can use goals to lead more effectively.

Use goals to set a benchmark for performance. A goal setting conversation should kick off the performance planning cycle – the what, when and how of performance. Help your employees set SMART goals: specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound.

Use goals to set a benchmark for performance. A goal setting conversation should kick off the performance planning cycle – the what, when and how of performance. Help your employees set SMART goals: specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound.

Engage employees fully in setting goals. Employee involvement creates more commitment to follow through. Don’t feel you have to mandate goals for your employees to prevent slacking. Research shows that most employees set challenging goals. Trust your employees. Treat goal setting as a dialogue rather than a top-down mandate. The goals that result will work well for you and your employees.

Make sure each employee has the right number of goals. Three goals will work well for many entry-level jobs. A retail sales person might have goals for sales volume, customer satisfaction and maintaining a clean sales area. A new manufacturing supervisor might have goals for production, quality and cost.

As an individual gains responsibility, the number and complexity of goals will increase. Use your goal setting conversations to lift their eyes to the new horizon. A new leader may be taking on people management for the first time. Help them set their own leadership goals. A new general manager’s goals need to be cross-functional and integrative. Help them set goals on profitability, innovation or stakeholder relations.

During the year, goals allow continuous improvement. Help your employees use data to unlock their habits. Just as you should have a leadership scorecard, encourage your employees to build a scorecard with metrics for their goals. Then, you can check in periodically to help overcome any blockades to performance.

At the end of the year, use goals to review performance. If goals have been the benchmark for performance and driver of continuous improvement through the year, the performance review should be straight forward. If an employee is not meeting their goals, you will need to manage the employee up or manage the employee out. You can focus on the required improvements, get specific about what changes are needed and (in the extreme) set a deadline for measurable improvement. However, if you lead with goals, most of your employees should be performing well. You will celebrate success together and renew the goals for next year.

Bottom line: As a leader, have a goal setting conversation with each employee at the beginning of the year. Encourage them to set SMART goals. Make sure each employee has at least three goals but not so many goals they are overwhelmed. Use their goals for continuous improvement throughout the year. And focus on performance against goals at the end of the year.

Help your employees get their goals right. If you lead with goals, your organization and your employees will benefit.

Unlock Your Habits With Data

Allen Slade

Leaders are creatures of habit. We hit upon a successful approach to communication, planning, decision making or hiring and we stick with it. Habitual behavior is very sensible. What worked yesterday is likely to work today. Yet, habits can become handcuffs. Habits may be comfortable and easy, but disaster looms around the corner.

As a leader, how do you know when to change? How do you unlock your habit handcuffs? You need data.

In the FIRST Lego League robotics competition, my sons’ team collected lots of data. They programed a wheeled robot to run a mission in 2 minutes and 30 seconds. The team spent months strategizing and reprogramming to beat the time limit. Data on the robot’s speed and reliability were key to continuous improvement.

In the FIRST Lego League robotics competition, my sons’ team collected lots of data. They programed a wheeled robot to run a mission in 2 minutes and 30 seconds. The team spent months strategizing and reprogramming to beat the time limit. Data on the robot’s speed and reliability were key to continuous improvement.

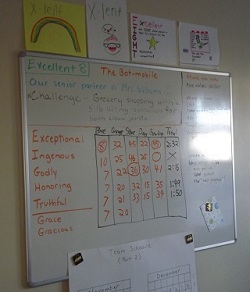

As a leader, you need data to know when your habits are ineffective. I advise you to build your own leadership scorecard. Track data on at least four different outcomes. Use a mix of “soft” data (employee and customer satisfaction, 360 data) and “hard” data (sales, costs, productivity and quality). If your organization produces reports for you, I encourage you to create your own leadership scorecard. If your organization doesn’t generate the data you need or if you are an entrepreneur, you may need to collect the data first.

You need to track these outcomes over time. Data from one point in time does not drive action nearly as well as trend data.

Once you have the data, build a spreadsheet or put it on a whiteboard. Avoid data overload by keeping your leadership scorecard focused. It should fit on a single sheet of paper or part of your whiteboard.

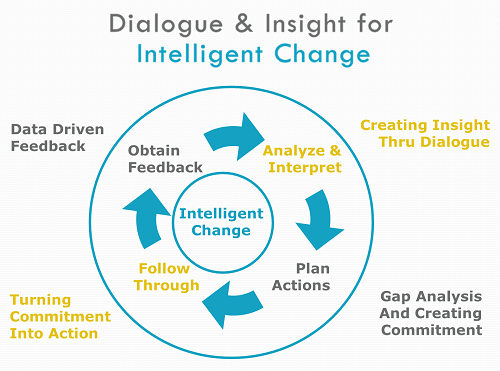

Once your scorecard is built, you are ready to start the cycle of intelligent change.

When your habits are not working, your scorecard will show it. Engage your team or your circle of trusted advisors in dialogue. Analyze the data and interpret the causes. Plan actions to fill the gaps and follow through. Then collect more data.

Bottom line: Leaders need to be data-driven. Create your own leadership scorecard to unlock the handcuffs of habit and reprogram your own behavior.

Create a virtuous cycle of intelligent change. Don’t wait for a crisis to look for numbers. Being data-driven should be your new habit.

Feedback Should be “Just Right”

Allen Slade

A careful reading of Goldilocks and the Three Bears suggests three lessons for leaders: Moderation in all things. Don’t be impulsive. Breaking & entering causes problems, especially at the Bears.

Previous posts have looked at The Problem with Feedback and Different Perspectives on Feedback. Today, we will consider moderation in two aspects of feedback. Instead of a single feedback cycle that may be too hot or too cold, just right feedback requires that you mix the timing of your feedback cycles. And, don’t just impulsively act on feedback. Use insight and analysis to balance openness to feedback with constancy of purpose.

Multiple Feedback Cycles

As a leader, you should be open to feedback because you need to know “When I walk in the room, who shows up for the other people?” You need to seek out feedback relentlessly.

But it is not enough to collect feedback tidbits. To drive intelligent change, you must analyze and interpret the feedback you receive. You must plan actions based on the feedback. You must follow through with your plans. Then, you must start the cycle again by collecting more feedback. If things are going well, continue on. If your feedback suggest things are not going well, change something – your follow through, your action plan or your analysis and interpretation of the feedback. This feedback cycle drives intelligent change.

How long should your cycle take? Consider feedback cycles of three lengths:

Long-cycle feedback. This is feedback on long term impact, such as data from the annual employee opinion survey or a 360 report. Long-cycle feedback looks at the sum of your actions over a period of time. Long-cycle feedback is typically generated by the organization with safeguards to increase its validity (e.g., anonymity) and relevance to organizational leadership (e.g., a competency model). Yet long-cycle feedback by itself is not enough to develop your leadership. The assessments underlying long cycle feedback are complex and open to rating errors. And, a leader cannot afford to wait a year to find out if leadership changes are effective.

Short-cycle feedback. This is feedback on a recent event, such as post action feedback right after a meeting. Short-cycle feedback looks at your actions in the very recent past. The advantage of short-cycle feedback is that it reduces the delay in adjusting a new behavior. The disadvantages of short-cycle feedback are often a lack of anonymity and a lack of structure.

The quick check-in is a useful form of short-cycle feedback. After a conversation or meeting, ask “How did today’s conversation (or meeting) go for you?” Most of the time, the answer will be “It went well.“ or ”Great.” In that case, continue on. Sometimes, you will hear something of incredible value. “We are bogging down in the data.” “To be honest, I was bored.” “You have spinach between your teeth.” Treat this feedback as a valuable nugget. Adjust the agenda, amp up the excitement or do a quick floss job.

Instant feedback. This is feedback in the moment, such as watching non-verbal language of others in a meeting or hearing a change in voice tone during a phone call. Instant feedback allows the leader to adjust on the fly. Instant feedback requires mindfulness of the cues that others give in the moment. It also requires the ability to multi-task by talking and watching, by focusing on your message and your impact on the other party, at the same time.

You need a mixture of these cycles. Instant feedback and short-cycle feedback, in excess, may be too hot. Long-cycle feedback, by itself may be too cold. But, combined in the right proportions, these different cycles can be just right.

Balancing Openness to Feedback with Constancy of Purpose

When you receive feedback, another form of moderation is needed. You need to consider the feedback before acting. In the heat of the moment, while receiving negative feedback, you can go overboard. You can impulsively agree to do everything the feedback giver wants. This strong desire to please can backfire. If you submit totally to the other person’s judgment, you undermine the powerful dialogue that should come with feedback. And, you subordinate your purpose to their goals for you. In effect, you jump from feedback to action plan without your own careful analysis and interpretation.

It is better to balance openness to feedback with constancy of purpose. The other person’s feedback is always valid and always valuable. Yet their goals for you may not be identical to your purpose. My advice is to accept all feedback from all willing parties, without necessarily submitting to their action plans for you. The balanced reaction to feedback is to listen, to learn and to engage the other person in mutual problem solving.

Back at the Bears

Let me close with another observation: Goldilocks had no support team for her decisions. Impulse can be moderated by wise counsel. Mixing feedback cycles is more complex than simply waiting for annual leadership feedback. Balancing openness to feedback with constancy of purpose is harder than a simple rule for action. I recommend using the power of collaboration to maximize the power of feedback. Work with your circle of trusted advisors, your mentor or your leadership coach to master feedback. Gather a support team to create dialogue and insight to drive intelligent change for your leadership.

Bottom line: As a leader, actively seek feedback. Gather the right mix of long-cycle, short-cycle and instant feedback. Balance constancy of purpose with openness to feedback. Gather your support team to get your use of feedback just right.

And don’t break & enter, especially at the Bears.

Different Perspectives on Feedback

Allen Slade

I see performance feedback sessions as an excuse for a great conversation. Not everyone shares my perspective. One manager at Microsoft gave performance feedback by Post-It note. The day of reviews, she got into work early and stuck a note on each monitor with a review score, merit pay, bonus and stock options. Then, she took the rest of the day off. I was aghast. In my mindset, this manager had great cowardice instead of a great conversation.

As a leader, have you been surprised at someone else’s approach to feedback? Suzanne Cook-Greuter lists seven ways to respond to feedback[1]:

Opportunist. Focuses on own immediate needs and opportunities. Values self-protection. Receives feedback as an attack or threat.

Diplomat. Focuses on socially expected behavior. Values approval of others. Sees feedback as disapproval or judgment.

Expert. Focuses on expertise, procedure and efficiency. Values expertise in self and others, but takes feedback personally as an attack on own expertise. Defends, denies, and delays feedback, especially from lesser experts.

Achiever. Focuses on delivery of results. Values effectiveness, goals and success. Accepts feedback if it helps achieve personal goals and improve effectiveness.

Individualist. Focuses on self interacting with the system. Individual purpose and passion are more important than the system. Welcomes feedback as necessary for self-knowledge and to uncover hidden aspects of their own behavior.

Strategist. Focuses on linking theory and practice. Looks for dynamic systems and complex interactions. Invites feedback for self-actualization.

Magician. Focuses on interplay of awareness, thought, action and effects. Values transforming self and others. Views feedback as natural and essential for learning and change.

Opportunists, diplomats and experts all have a problem with feedback. They resist negative feedback, breaking the cycle of intelligent change.

Today’s post focuses on achievers, individualists, strategists and magicians who all share an openness to feedback. Let’s look at each in detail:

4. The achiever wants to win – accomplish the goal, launch the product, land the contract. An achiever looks for a score, a time, or an amount; in other words, feedback that defines achievement. The achiever mindset seeks success within the status quo, like Zaleznik’s “manager.” The achiever plays the feedback game to win.

5. The individualist wants personal growth. Feedback is welcomed because it triggers growth and change. The individualist can return to the mindset of an achiever, going full speed after goals. But the individualist sees self-purpose as more important than the rules of the system. The individualist challenges the status quo, like Zaleznik’s “leader.” The individualist wants to fix the feedback game to make it better.

6/7. The strategist and the magician play the feedback game at a higher level. Instead of a single loop of feedback and action planning, strategists sees interconnected loops with multiple points of contact and causality. When I play Monopoly, I see math skills for my kids to develop, political dynamics for them to perceive and opportunities for them to make SMARTer requests. (At the same time, the individualist in me wants to grow as a parent and the achiever in me wants to win!) The magician sees feedback as integral to all healthy systems, so they create feedback loops, building systems on top of systems.

Bottom line: People think about feedback differently. Know yourself. Know how the people around you react to feedback. Adjust to maximize your influence.

Know yourself. As a leader, know your own mindset in accepting feedback. Which is your typical response to feedback? When you are at your best, what is your response? Your reaction to feedback depends in part on your mental and emotional state.

When I am caught off guard by negative feedback, I tend to react as an expert – defend, deny, and delay. If caught off guard, I try to say “This seems important. Can we talk about it tomorrow?” By delaying (instead of denying or defending), I can receive feedback when I am at my best. Know your triggers for ineffective responses to feedback and work around them.

Bridge to your employees. As a leader, you need to bridge between your mindset and the mindset of your employee. Bridging may involve translation, empathy and a mixture of resolve with patience.

Leaders often give performance feedback expecting the employee to react with an achiever’s mindset. The employee, with an expert mindset, sees the leader as a lesser expert with out-of-date skills and little sense of the actual job. The leader gives achievement-oriented feedback and the expert employee defends, denies or delays. The feedback meeting goes from bad to worse, because manager and employee both believe the other is naive, wrong or worse.

Translate your feedback into your employee’s mindset. In giving feedback to an expert, call on your expertise as a manager. “You know more about your job than me, but I know how management thinks.” If your employee is a diplomat, avoid judgmental words. “Let’s help you fly under the radar in the future.”

Be empathetic. Every mindset is built on all the earlier mindsets. If you are an achiever and your employee is an expert, regress a bit. Remember how to think as an expert and go from there.

Mix resolve and patience. Stick to your guns, but give your employee time to come around. Give continuous feedback so there are no surprises.

Bridge to your boss. As a leader, you and your boss may not share the same feedback mindset. If your boss is at an earlier feedback mindset than you, use translation, empathy, resolve and patience. If your boss is at a later feedback mindset than you, translation and empathy will be tougher because you don’t grasp their mindset yet. Be patient. Resolve to listen and learn so you can grow to think about feedback like they do.

People think differently about feedback. As a leader, bridge these differences with translation, empathy, resolve and patience.