When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Too Many Goals?

Goals are powerful leadership tools. They focus attention and effort on the key accomplishments needed for organizational success. If goals are good, are more goals better? As a leader, how many goals should you set?

Basics of Goal Setting

As a leader, goal setting is an essential part of your leadership toolbox. Like any tool, you have to use goals right:

Set SMART goals. Smart goals are specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound.

Coordinate goals. Use management by objectives to ensure goals are coordinated between people and organizations.

Provide metrics. Give goal-specific feedback to further shape and refine behavior. I will discuss metrics more in my next post.

No Goals are No Good

Leadership is managing energy in yourself first and then in others. Goals help you manage energy. Goals provide a destination for efforts. They give direction and quantity for work related behaviors. If you have no goals, your own efforts will be unfocused. And if you do not set goals with your team, their efforts may be unfocused also, or their efforts may be focused on things that do not contribute to the organization’s success.

Too Many Goals

Goal setting is good, but be careful. Too many goals can backfire. The key benefit of a goal is to focus energy. More goals create more focal points. Like a busy instrument panel, too many goals can confuse and distract rather than focus attention.

So, how many goals is too many?

More than three goals is the same as no goals. When a client asks how many goals to set, I use this simple rule of thumb as a starting point.

A simple rule of thumb is better than nothing, but principles of leadership are outdated. Here are more refined ways to think about the maximum number of goals.

More goals with experience. An experienced pilot shouldn’t have trouble making sense of a plane’s control panel. An employee with years of good performance can handle more than three goals.

More goals with phased timing. If you have a complex project, a project plan might have dozens or hundreds of task goals. So long as your employee understands the project plan, the number of goals will not be an issue.

More situational goals. Some goals are relevant only in certain situations. For a retail business, you might have a SMART goal about customer wait times. If customers are not waiting, that goal is not triggered. You can have other goals about stocking or cleaning that are triggered in other situations.

In other words, the maximum number of effective goals depends on the situation your employee faces. To really know how many goals, you should have an ongoing dialogue about goals with your employees.

Goal setting. At the beginning of the performance cycle, set goals participatively. Get your employee’s sense of what is realistic.

Goal performance. While the goals are in place, keep the conversation going. Get to know their work pace and their motivations. Adjust goals as needed, whether it is the type of goal, the level or the number of goals.

Goal review. At the end of the performance cycle, evaluate performance against goals. And also evaluate the goals themselves. Ask how the goals helped or hindered performance. And be open to correcting your missteps in setting goals or supporting your employee’s performance.

Throughout the goal cycle, keep the conversation going. And, make it a dialogue. Actively listen as much as you speak.

Bottom line: Know how many goals is too many. Understand the situation each employee faces and work with them to set a realistic number of goals. And, if you have created too many goals for an employee, back off. Prioritize and consolidate goals to get the right number of goals. You will help your employees focus their attention and increase their performance.

Images of Active Listening

From my series of blog posts on active listening for leaders.

.

.

Listening in the Performance Valley

Listening in the Performance Valley

.

Energy for Active Listening

Leaders who listen well are more effective, more persuasive and more engaging than leaders who don’t listen. Carol Wilson¹ lays out five levels of listening:

1. Interrupting

2. Sharing

3. Advising

4. Attentive Listening

5. Active Listening

We have thought about Levels 1-4 in previous posts.

- You’re not listening if you’re interrupting, sharing or advising (Levels 1, 2 or 3).

- Attentive listening (Level 4) can be effective, especially in the midst of change.

Today, let’s complete the set by looking at active listening (Level 5) in more detail.

5. Active Listening

“I had the worst meeting with my boss today.”

“What happened?”

“She tore apart my financial report. I was embarrassed in front of everyone.”

“That must have been difficult.”

“You don’t know the half of it.”

“Has this happened before?”

. . .

“Why do you think she reacts that way?”

. . .

“Have you thought about what you can do?”

Active listening takes your leadership to the next level. Like attentive listening, you are focused on the other person and what they say. But you are adding more breadth and depth to the conversation. I define active listening as “the art of listening with intensity to truly hear what the other person says, knows and feels.”

The conversation about the meeting disaster gets to the heart of the issue. The other person’s feelings are validated with the reflective statement “That must have been difficult.” Causality is explored with the “Why?” question. And the other person’s problem solving is activated by asking “What can you do?”

Just the Facts?

Both attentive listening and active listening are powerful and effective tools for a leader. Both focus on the other person and help them make sense of their situation.

So what’s the difference? For me, attentive listening focuses primarily on the facts of the situation. An attentive listener asks “Who? What? Where? When?” Active listening goes beyond the facts to get to reactions and feelings. Active listening consciously explores causal factors and engages the problem solving capabilities of the other person. An active listener asks “Why? How? What’s next?”

Attentive listening focuses on the words of the other person. The active listener goes beyond just the words to notice tone, facial expression and body language. Carol Wilson describes active listening as “listening behind the words and between the words; listening to the silences; using your intuition; promoting the coachee to explore; facilitating the coachee’s self learning and awareness; making suggestions.”

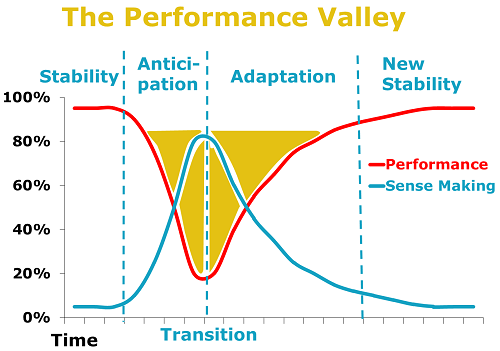

If attentive listening can help shrink a performance valley, active listening is even better. When you actively listen, you have a greater opportunity to address feelings, explore causes and get the other person to solve their own problems. Then, you maximize their sense-making in the midst of change and help them get back to peak performance sooner.

Managing Your Energy

Active listening is powerful and effective. That power comes from your intensity and focus. But expending that level of power can drain your battery.

Bottom line: Active listening is hard. In a classroom exercise, I ask my students to actively listen for seven minutes. Maybe one student in thirty can actively listen for seven minutes.

Don’t be discouraged if you have trouble staying in active listening mode. Like most leadership skills, you can improve your capacity for active listening with practice. If you’re new to active listening, start small. Try this mini-experiment:

- Find someone who needs to talk. Then listen as intensely as possible for ten minutes. Notice how much time you spend in interrupting, sharing, advising, attentive listening and active listening.

- Repeat with another 10 minute listening session. Try to increase your time in active listening. It’s ok to dip into attentive listening, but minimize your interrupting, sharing and advising. Again, notice how much time you spend in each listening level.

- Keep looking for listening opportunities, gradually increasing your proportion of active listening. Then, plan to listen for 15 minutes.

With enough practice, you can achieve 50-70% active listening for an hour.

If you’re already competent at active listening, I encourage you to listen more and better. Increase your active listening capacity like a miler training for a marathon. My mini-experiment in active listening has been going for years. After every coaching session, I still do a self-evaluation of my listening. I am getting better, but I still have a way to go.

Novice or expert, practice will build your listening capacity. And, if you listen carefully, you may notice a few performance valleys shrinking.

______________________

¹Carol Wilson, “Tools of the Trade” Training Journal, July, 2010, pp. 65-66.

Listening in the Performance Valley

Listening is a key skill for leaders. Leaders who listen well are more effective, more persuasive and more engaging than leaders who don’t listen.

Listening is especially useful when the other person is trying to make sense of change. Anticipating and adapting to change requires substantial cognitive effort – what I call sense-making. Sense-making creates a performance valley during change.

A leader who effectively listens can accelerate the other person’s sense-making. That gets them out of the performance valley quicker.

Listening requires you to be quiet and focus on the other person. Carol Wilson¹ lays out five levels of listening:

1. Interrupting

2. Sharing

3. Advising

4. Attentive Listening

5. Active Listening

For levels 1,2 and 3, you’re not listening if you’re interrupting, sharing or advising. Attentive listening and active listening are both ways to truly listen. Today, let’s look at Level 4 – attentive listening.

4. Attentive Listening

“I had the worst meeting with my boss today.”

“What happened?”

“She tore apart my financial report. I was embarrassed in front of everyone.”

“Who else was there?”

. . .

“What did your boss say about the report?”

With attentive listening, you focus on the other person and what they say. You notice their words and ask on-target questions. You help the other person pull their thoughts together. As Karl Weick says “How can I know what I think until I see what I say?” Attentive listening keeps them talking, helping them to know what they think with more breadth and clarity.

So, how can you listen attentively?

- Focus on the facts of the situation. An attentive listener asks “Who? What? Where? When?”

- Pause. Attentive listening requires you to focus on the words of the other person. Go slow enough to truly listen. Don’t plan your next question while the other person is talking. Listen to what they say, then compose your question.

- Allow the other person to pause also. If they are silent after you ask a question, be patient and allow them to think.

With attentive practice, you can become a powerful listener. And, if you listen carefully, you may notice a few performance valleys shrinking.

______________________

¹Carol Wilson, “Tools of the Trade” Training Journal, July, 2010, pp. 65-66.

You’re Not Listening

Active listening is a key skill for leaders. In a previous post on Two Steps to Active Listening, I defined active listening as “the art of listening with intensity to truly hear what the other person says, knows and feels.” Leaders who actively listen are more effective, more persuasive and more engaging than leaders who don’t actively listen. It is good to know what active listening is. It is also good to know what active listening is not. Let’s look at other ways to listen.

Carol Wilson¹ lays out five levels of listening:

2. Sharing

3. Advising

4. Attentive Listening

5. Active Listening

The first three levels don’t contain the word “listening” for good reason: When you’re interrupting, sharing or advising, you’re not listening.

Levels 4 and 5 are truly listening, and we will talk about them in a later post. Today, let’s look at levels 1, 2 and 3.

1. Interrupting

“That really didn’t go well. I am worried about . . .”

“Did you see the game last night? The officiating was awful.”

When you interrupt, you build yourself up at the other person’s expense. In effect, you are saying “Be quiet because what I have to say is more important.”

How often do you interrupt others? Maybe you are rushed, anxious or annoyed. Maybe the other person has raised a topic you want to avoid. Whatever the reason, you drain energy by stepping on their airtime. A little patience, a bit of deference and a dose of etiquette will make you a better listener and a better leader.

2. Sharing

“My boss always takes credit for my work. It’s just not fair.”

“Yeah, he did the same thing to me. I made this killer presentation, but he just put his name on it and presented to the vice-president.”

With sharing, when someone shares their experience, then you share a similar experience. You may think you are reinforcing their experience, but you are really minimizing their unique situation. When the other person is speaking, you are focused on preparing your response. In other words, you are silent but not listening too hard.

When you appear to be listening, are you just waiting your turn? Do you value your experiences more than the experiences of the other person? Serve the other person by focusing on their story – your story can wait.

3. Advising

“I get really nervous when I present to the Design Group. Sometimes I shake like a leaf.”

“Try practicing in front of a mirror.”

As an accomplished professional, you have experience, expertise and insight. When someone presents you with a problem, it is easy to shift into problem solving mode.

As a problem solver, listening is critical to help you diagnose the situation so you can provide the best solution. However, it is tempting to listen only enough to figure out the problem. If your default listening mode is advising, then listening can come across as a necessary evil rather than a worthy pursuit.

Problem solving is a good thing. The problem with problem solving is we use it too much and we use it too soon. We present solutions when the other person needs dialogue. We jump to solutions instead of deep-diving issues, understanding values and exploring causality.

If someone presents you with a problem, do you quickly offer a solution? Do you listen just enough to be confident in your solution? Listen more – it will lead to better solutions. Listen longer – the other person may solve their own problem. Listen better – it will show you care.

You’re Not Listening

Interrupting, sharing and advising have two common roots. The first root may be your self-confidence. You value your own experiences, insights and problem solving capability. However, your self-confidence may bulldoze the other person’s need to be heard.

The second root may be your lack of confidence in the other person. Their conversation may show immaturity. Their wisdom seems lacking. They, after all, have come to you. If you lack confidence in them, it logically follows that you will talk more so they will talk less.

Whether you suffer from too much self-confidence or too little confidence in the other person, the end result will be too little listening on your part and too much interrupting, sharing or problem solving.

Listening Starts With Humility

The best listeners are humble. They value the other person highly. They have patience because they know the other person has important things to say. The best listeners serve by having more questions than answers. And, they would rather help the other person solve their own problems.

Notice how you listen. Notice when you shift to interrupting, sharing or problem solving. If your interruption, your story or your solution does not serve the other person, then I will give you Bob Newhart’s classic advice: stop it.

Instead, take the two steps to active listening: be quiet and value the other person. You may find the resulting dialogue leads to better insight, better solutions and a better relationship.

______________________

¹Carol Wilson, “Tools of the Trade” Training Journal, July, 2010, pp. 65-66.

Two Steps to Active Listening

Listening skills are critical for leaders. Listening opens the channels for two way communication. And it is not enough to simply be present when others are talking. You must engage in active listening, the art of listening with intensity to truly hear what the other person says, knows and feels.

I have coached b-school students, change management clients and leadership coaching clients on how to listen better. Based on those experiences, here are two steps for active listening.

1. Be Quiet

The first step to active listening is simple. Stop talking. Let the other person speak without interruption or comment from you. Surprisingly, this step is often the hardest, especially for people who are smart, driven and successful.

Sometimes we act as if silence implies consent. When someone says something wrong or they focus on unimportant aspects of the issue, we want to jump in to set things right. But you can hear without necessarily agreeing. Like a reporter interviewing politicians or a researcher gathering consumer opinions, you might not agree with what is being said, but you can stifle your impulse to speak in order to truly understand the other person’s point of view.

There is another reason to be quiet. Silence is power. In most social situations, we expect talking to fill every moment. Your silence implies personal control. Being silent means you are confident and comfortable. If you can be quiet, the other person may feel compelled to fill the uncomfortable silence.

2. Focus on the Other Party

The point of active listening is to get the other person’s perspective. To do that, you must focus on them – completely.

Use reflective listening. Repeat and paraphrase what you hear. Use phrases like “I hear you saying…” or “It sounds like…” Ask questions of clarification like “Why do you think that happened?” “When did she first say something?” or “How did that work out?” Summarize their key points. When they have given you lots of facts and reasons, try to draw out the themes. And be tentative, always checking with them to see if you understand what they are trying to say.

But it is not enough to listen to the other person’s words. You must also watch their non-verbal communication. Watch facial expressions, tone of voice and body language. Check your observations by using the phrase “You seem to feel . . .” It is especially important to notice when their words and their non-verbal communication seem to be at odds. For example, if the other person tells you they fully support a certain decision (while their eyes are downcast, their voice has no energy and their posture is slumped), follow up to see if there are some unspoken concerns.

A Difficult Conversation

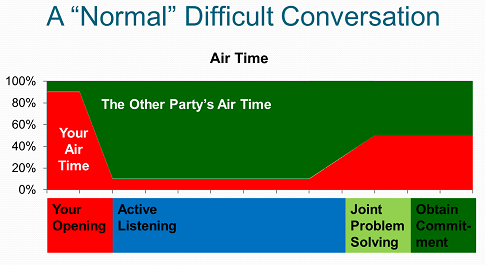

Suppose you need to have a difficult conversation with someone. You may need to discuss a broken commitment, call out unacceptable behavior or give feedback on poor performance. While you might think talking more increases your chance of persuading them, you might be surprised by the power of active listening. The best difficult conversations follow this pattern:

Active listening is central to this difficult conversation. By being quiet and focusing on the other party, you are helping move them toward joint problem solving and commitment. Your active listening helps them process the difficult topic. You are gaining credibility by listening. And, you will actually learn their perspective, which may change your mind about the situation and the other person.

Active listening is central to this difficult conversation. By being quiet and focusing on the other party, you are helping move them toward joint problem solving and commitment. Your active listening helps them process the difficult topic. You are gaining credibility by listening. And, you will actually learn their perspective, which may change your mind about the situation and the other person.

Difficult conversations require wisdom. Active listening is a great way to be wise. “Whoever restrains his words has knowledge, and he who has a cool spirit is a man of understanding.”¹

If you are like me, you sometimes struggle with difficult conversations. Active listening is a great way to fake wisdom. “Even a fool who keeps silent is considered wise; when he closes his lips, he is deemed intelligent.”²

A Gift

Many people live in a cone of silence. They go through most days without being heard, without being really listened to. As a leader, you can give a few minutes of your time by actively listening to the people you lead. The benefits to them and to your organization will be worth your time.

__________________________

¹Proverbs 17:27

²Proverbs 17:28

Leading Change for the Net Gen, PC Gen and TV Gen

Allen Slade

In a post on Digital Deception Detectors, I contrasted two views of technology:

The Net generation integrates technology fully with relationship. They adopt new technology for coolness, using Facebook (or Twitter or Pinterest or whatever) because their friends do. Using a network multiplies their friends on the network.

The PC generation sees technology as a tool. They master new technology to get things done. They aren’t early adopters. They won’t upgrade Windows or switch from email to Facebook without a good reason. They want a tested version of new technology, with no bugs and a good help function.

Here’s a third perspective:

The TV generation passively accepts what technology offers. They change the channel or dial the phone, but they allow other to create the channels and content. If technology does not work, they look for an expert or give up. They tend to be late adopters, mastering new technology under direction or duress. Once they have mastered a technology, they use it habitually.

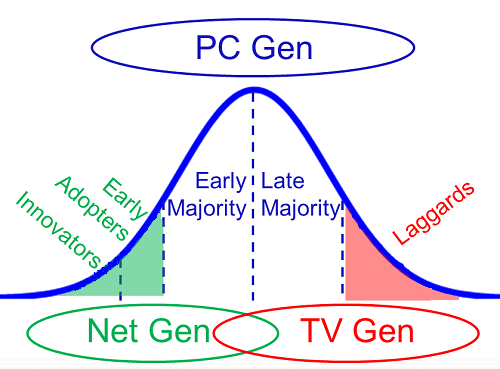

Geoffery Moore categorizes people by how quickly they accept new technology – from early adopters to laggards.

The difference between Net, PC, and TV generations is not necessarily how quickly people adopt new technology. The difference is how and why people use technology. The Net gen asks “What’s cool? How can I connect to friends?” The PC gen asks “What works? How can I get stuff done?” The TV gen asks “What’s on tonight?”

As a change leader, how should you interact with the three generations?

The Net generation treats technology as a natural part of life. They can be the easiest to lead becasue they are are comfortable with technology change. However, they can be cynical about large organizations and their leaders. Their digital deception detectors are tuned for any sign of inauthenticity.

Microsoft’s old advertising slogan “Where do you want to go today?” worked well with the PC gen, but the Net gen’s reaction was “Riiight. Bill Gates, the richest man in the world, wants to help me accomplish my goals.” Trip their digital deception detector and you’ll lose the Net gen.

The PC generation has a utilitarian relationship with technology. They would rather not upgrade to the latest version of Office or change from email to Facebook unless there is a good reason. When getting their buy-in, leaders should focus on the great things they can do with the new system.

When we converted to a new web-based survey system at Ford Motor Company, our audience of executives and HR professionals were largely PC gen. Our key message: Better, Faster, Cheaper. We reduced turnaround time and costs, music to the ears of the PC gen.

The TV generation has a passive relation with technology, expecting to absorb what is transmitted. They can resist learning new technology that requires their active involvement. The TV gen may require a lot of persuasion, to the point of coercion.

One of my colleagues launched an executive information system restricted to vice presidents (no executive assistants allowed). One third of the vice presidents never logged on. They want their reports delivered to them, like turning on the television. The CEO decided to guide the non-users to leave the company as soon as possible. My colleague’s take “If you can’t change the people, sometimes you have to change the people.”

Bottom line: You can lead change across the generation gaps. For the Net gen, be authentic. Emphasize the coolness and connectivity of the technology without triggering their deception detectors. For the PC gen, focus on achieving business objectives. Be persuasive about the value of change. For the TV gen, confidently lead the change. This may mean directing the laggards to comply or leave.

Put it all together, and you will have authentic, goal driven and confident leadership of change. That’s the type of leadership all generations can get behind.

How’s Your Digital Deception Detector?

Allen Slade

Catfishing entices a dupe to befriend a fake person, to the victim’s embarrassment. Notre Dame football player Manti Te’o used his girlfriend’s death to propel his team to the national championship game. When this girlfriend turned out to not exist, he claims to have been duped.

Was Manti Te’o a victim, part of the scheme or a little of both? How could credible sports reporters feature this emotional story without checking their facts?

Leaders must be masters of the digital divide that catfishing exploits.

The PC generation sees technology as a tool. They master new technology as necessary to get things done. They tend not to be early advocates of new technology. They would rather not upgrade Windows or switch from email to Facebook unless there is a good reason. They want a tested version of the new technology, with no bugs and a good help function.

The Net generation integrates technology fully with relationship. They may be early adopters of new technology, but they adopt it for coolness as much as utility. Their choice of media is driven by relationships. They use Facebook (or Twitter or Pinterest or whatever) because many of their friends do. And, their use of a network creates more friends on that network.

One of the differences between these generations is how they avoid deception in digital relationships – the problem of Manti Te’o’s nonexistent girlfriend. The PC gen avoids deception by limiting true relationships to people they have met face-to-face. They might think Manti is a fool for having a girlfriend he never met. The Net gen does not limit friendships to the physical world. Instead, they survive and thrive in the virtual world by developing finely tuned deception detectors. They might think Manti Te’o is a fool because his digital deception detector failed.

The PC gen and the Net gen can be hard to tell apart. They both use smart phones and tablets, Facebook and Twitter, Excel and WordPress. And, a 70-year old can be in the Net gen while her grandson is in the PC gen. Manti may be a Net Gen’er who duped PC Gen sports reporters until things spun out of control. Or he may be a PC gen’er whose use of network technology was naïve.

As a change leader, how can you tell them apart? I ask a single question: “Do you have close personal friends that you have never met face-to-face?”

- PC gen: “Are you kidding?”

- Net gen: “Yes”, with active digital deception detector.

- Future catfishing victim: “Yes” but lazy or clueless about digital deception.

As a leader, you must navigate the digital divide between the PC generation and the Net generation with agility and authenticity.

If you are of the PC generation, master the new technology and find friends you will never meet face-to-face. Go slowly to avoid being catfished. Don’t propose marriage but do corraborate any funeral notice. (You can practice with me – Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn buttons are at the top of this page.)

If you are of the Net generation, bring the PC generation along by appealing to the utility of the networked world. Help them avoid being catfished. Appreciate and honor their desire for face-to-face contact.

Whichever side of the divide is your native land, mediate the conflicting world views with authenticity. Then, you will be able to get everybody on board with your larger purpose.

Unlock Your Habits With Data

Allen Slade

Leaders are creatures of habit. We hit upon a successful approach to communication, planning, decision making or hiring and we stick with it. Habitual behavior is very sensible. What worked yesterday is likely to work today. Yet, habits can become handcuffs. Habits may be comfortable and easy, but disaster looms around the corner.

As a leader, how do you know when to change? How do you unlock your habit handcuffs? You need data.

In the FIRST Lego League robotics competition, my sons’ team collected lots of data. They programed a wheeled robot to run a mission in 2 minutes and 30 seconds. The team spent months strategizing and reprogramming to beat the time limit. Data on the robot’s speed and reliability were key to continuous improvement.

In the FIRST Lego League robotics competition, my sons’ team collected lots of data. They programed a wheeled robot to run a mission in 2 minutes and 30 seconds. The team spent months strategizing and reprogramming to beat the time limit. Data on the robot’s speed and reliability were key to continuous improvement.

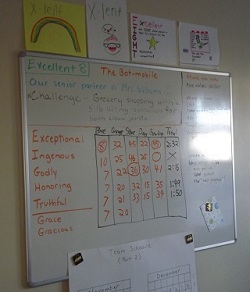

As a leader, you need data to know when your habits are ineffective. I advise you to build your own leadership scorecard. Track data on at least four different outcomes. Use a mix of “soft” data (employee and customer satisfaction, 360 data) and “hard” data (sales, costs, productivity and quality). If your organization produces reports for you, I encourage you to create your own leadership scorecard. If your organization doesn’t generate the data you need or if you are an entrepreneur, you may need to collect the data first.

You need to track these outcomes over time. Data from one point in time does not drive action nearly as well as trend data.

Once you have the data, build a spreadsheet or put it on a whiteboard. Avoid data overload by keeping your leadership scorecard focused. It should fit on a single sheet of paper or part of your whiteboard.

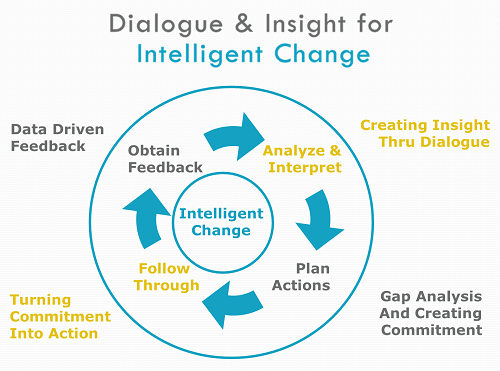

Once your scorecard is built, you are ready to start the cycle of intelligent change.

When your habits are not working, your scorecard will show it. Engage your team or your circle of trusted advisors in dialogue. Analyze the data and interpret the causes. Plan actions to fill the gaps and follow through. Then collect more data.

Bottom line: Leaders need to be data-driven. Create your own leadership scorecard to unlock the handcuffs of habit and reprogram your own behavior.

Create a virtuous cycle of intelligent change. Don’t wait for a crisis to look for numbers. Being data-driven should be your new habit.

When Your Personal Brand is Your Business Brand

Allen Slade

The essence of your personal brand is simple: When you walk through the door, who shows up for the other people in the room? As a jobseeker, your personal brand captures the service you are offering to an employer. As a leader, your personal brand is the influence you exercise in driving innovation and growth.

How about entrepreneurs? As the boss, you aren’t a jobseeker trying to nail the interview or an emerging leader trying to get people to start following you. Entrepreneurs are busy with operations, finance and market development, so “personal branding” may seem like a waste of time.

Wrong. Personal branding is vital to entrepreneurial success. When you are an entrepreneur, you are your business. When you market your business, especially in the early years, you are marketing yourself. In many ways, your personal brand is your business brand.

At one of my recent personal branding seminars, a twenty-something woman shared her passion and unique business model. However, she was outfitted and groomed for comfort rather than marketing, undermining her great ideas.

So, who shows up for your prospects when you walk in the room? Do you project the traits necessary to win their business? Here are some hints on developing your personal and business brand.

Be authentic. Make sure your personal brand is completely compatible with the real you. And make sure your business fits you as well. Being authentic ensures you (and your business) will avoid false advertising. If your brand promises what you can actually deliver, you and your customers will prosper.

Project an integrated image. This is Branding 101. Once you have specified your desired brand, review every part of your public image to make sure it is consisted with your brand. Review everything: marketing strategy, service offerings, elevator pitch, brochures, website, blogs, business cards, LinkedIn profile, Facebook page, Twitter profile and tweets.

Test and adjust your brand. Get feedback as you roll out your brand. You want to test an ejection seat before you need it. So test your brand privately before you go public with it. Early on, test your brand with yourself. Adjust your public materials to fit your brand statement, and adjust your brand statement to fit your previously successful public materials. Next, run your proposed brand by your circle of trusted advisors. Hand out business cards to friends and family. Practice your elevator pitch. Ask people what they think. Then, do a small scale public unveiling. Pilot test your newly articulated brand with both prospects and trusted current customers. Get their feedback and continue to adjust until you hit a sweet spot – a brand that is personally authentic and offers compelling benefits to your customers.

At the branding seminar, I offered one more piece of advice:

Dress (slightly) better than your customers. I recommend that you dress one half step better than your customers. If they wear business casual, you iron your khakis and polo. If they wear a blazer, you add a tie. If they have a skirt, you were a dress or suit.

The twenty-something entrepreneur caught the personal brand bug. She emailed the next week about changes she was making in her brand image. “I’m trying to dress more professionally these days. Sounds simple, but for me, it’s really hard. Especially the whole ‘make-up’ thing!”

While you may not struggle with make-up as part of your personal brand, you will struggle. Your brand is the essence of who you are and the value you add to the people around you. Getting it right requires time, energy, thought and feedback. And, when it clicks, you and your business will succeed.